Hello! Exciting Announcements for The Book of Ptah!

I am introducing a new section where YOU can become a part of this Substack. I’ll be featuring guest posts that align with the spirit of this space.

The first guest post is by

and there are more to come.Much like the endless toil of Sisyphus, forever pushing the boulder up the hill only to see it roll back down, our experiences with the rise of technology and the internet mirror a similar journey. The pre-internet era felt like a time of simplicity, an uphill climb grounded in tangible connections, physical books, and face-to-face conversations. Each generation had its own unique struggle and its own moments of fleeting accomplishment, much like Sisyphus with his stone.

As I invite you to contribute to Sisyphus’ Journey, sharing stories from before the internet and your early digital days, there’s an opportunity to reflect on the ways this "boulder" of technology has reshaped our lives. Did it open new vistas, or did it feel like a relentless cycle of scrolling and searching, always seeking meaning, only to have it slip away again?

Your contributions will be personal, rooted in your own experiences—offering wisdom to my generation. In a way, we are all on this Sisyphus’ journey, facing an ever-evolving landscape of innovation and loss, progress and nostalgia, continually pushing forward while looking back at what once was.

Maybe we end up learning something from each other.

Introduction to a collaboration between Ashutosh Joshi and myself.

I met Ash in Jodhpur, as some of you may remember from my post (if not read it now, it’s one of my better ones) back aways. He set up his substack shortly after our meeting and is already heading for 1000 subscribers, plus he has written and self published an excellent book - Journey to the East - about his walk across India which you can buy by clicking the link.

Ash, being young and nimble of mind, discovered you can collaborate with other writers on here and suggested the subject of life before the internet for me, and, obviously, life after for himself. Other people are being invited to muse on this subject too. Frankly I could write a book on it (there’s an idea?), but below is an attempt to put the birth of the internet as we now know it into the context of my day to day reality at the time.

There is no way now to reverse it, too late to put in place safety mechanisms to stop the dark side emerging as it has, or give it a place side by side with the old fashioned way of learning and being in nature. It has given so much to us —not least platforms like this— but it also takes so much away.

Ash’s view of the world is not only from a different generation but from a culture totally different from mine. I look forward to reading his take on this subject, and the other collaborators he has invited, but for now here is mine.

Life Before the Internet

When was that exactly? Before 2000? 1999? 1995? I honestly don’t know, but obviously, I will now look it up because I have, at my literal fingertips, the means to find answers to everything—well, everything that has been documented by humans for whatever reason.

Ok, so I looked. Lots of words and swimmy eyes almost immediately, but it seems that it started as far back as 1959. For home use, it was the early '90s, with dial-up and then broadband. I remember getting my first email account set up on my brand-new Dell computer in the flat I shared with my three-year-old son, and that distinctive, distant-sounding binkling that signified logging on. Dell was a sideways move in an otherwise Apple Mac addiction. I find Apple more intuitive, and you get less junk. That said, I dislike the corporation intensely, along with all other corporations that exist purely to make money for shareholders with little or no concern for the end users or, more importantly, the planet. The end users do actually have a choice, the planet does not.

So, back to pre-internet days. I yearn for them in the same way I yearn for warm, sunny summers and crisp, clean, cold winters. Is it pure nostalgia? Looking back with rose-tinted glasses? I don’t think so, not entirely anyway.

We all look back to our childhoods—those of us who were lucky enough to have had one, that is—with a sense of nostalgia and a wish to return to simpler times. Someone bought your clothes for you, put food on the table at a certain time. School was a drag, but it’s where all your friends were.

I was born into a large, unruly Catholic family in rural Yorkshire with, my brother describes, complicated parents. But when I was very young, I had no concept of complicated. Reality was the now: the hugs, the cuffs from big brothers, the food, the noise, lovely hand-me-down dresses from my posh cousins, and lovely hand-me-down scruffy jeans from my brothers, the routine of home and church.

We were not allowed comics, except on train journeys, so I read books. I read every single one of the Andrew Lang fairy books and entered that world of kings and giants, princesses and goblins, evil stepmothers and impossible tasks set by entitled demagogues, followed by swift and violent justice dispensed by the smug prince or witch with absolute focus. The illustrations by Henry J. Ford are some of the most detailed and wonderful I have seen anywhere.

My brother Luke rather obnoxiously read all three books of The Lord of the Rings trilogy by the age of 10. I still haven’t managed it, but this is to illustrate the kind of material we had on hand as a middle-class, bookish family. There were other books, more ‘modern’ ones, like Family from One End Street (I was intrigued by the idea that houses could have numbers, as we didn’t have one, nor did any of our neighbors) by Eve Garnett and Ballet Shoes by Noel Streatfield, which still holds an enduring place in my affections for the fantastic characters and plotlines.

We didn’t have a TV until I was about eight. We finally got one as a gift from Germaine Greer. She and my mother were on a panel for something or other (no doubt a Catholic thing, as that was GG’s origin too), and while chatting about personal stuff afterward, Mum told her how we were given a choice between having a swimming pool or a TV. Naturally, being summer, we chose the swimming pool. It was one of those tin-sided things that you bolt together and line with pale blue plastic. It was fantastic for making whirlpools, but then autumn came.

GG was treating herself to a colour TV and offered to send us her old black-and-white one. We were transported with joy. The huge box arrived, we opened it, and the TV was placed on a shelf in the playroom, where it was worshipped by bug-eyed children. Mum bought the Radio Times (a habit she kept up until her death at 97 earlier this year), which at the time only had BBC listings, and circled the things we could watch—one thing per day. If we wanted to watch Top of the Pops and The Goodies (both on the same night), we would sit behind the TV shelf, listening to the music and sneaking peeks, and then fully watch The Goodies—who can resist such madness, especially when it involves a giant kitten? We weren’t allowed to watch ITV because of the adverts.

So, that was my childhood. My teen years were disjointed in many ways. I wandered through them via various schools, living between my family’s new home in Scotland and my cousins' home in Surrey when I wasn’t at boarding school. I’ve seen films where teenagers are always on the phone with each other after school, sometimes even having their own phone in their bedrooms. I didn’t do this and felt no need to. Occasionally, I would be in touch with school friends by phone during the holidays, but my main method of communication was by letter. That’s how everyone I knew communicated. Even when there wasn’t much to say, not unlike those phone calls, I’m guessing. A school friend had a typewriter at school, which I loved to write with—it somehow gave me more freedom with my words. Eventually, I got one of my own, given to me by my brother, who had been gifted it by his boss at the Press Association when they upgraded their equipment. It was huge, bulky, and incredibly heavy. I loved it. I took it to art college and lugged it around various bedsits and shared houses, along with an old radiogram I had picked up at a jumble sale. They were my two pieces of furniture. I don’t know what happened to either item.

As I grew older, finished college, and moved to London, a natural kind of shedding of people I had known began. Not intentionally—it just happened. A letter would go unanswered, another house move made traceability harder, new people entered my life, new interests arose, and perhaps even love, which, as we all know, obliterates the need for anyone or anything else, for a time.

You can help Lizzy by buying her a coffee here..

Keeping in contact with people became more of a chance thing. Sometimes I would wonder about so-and-so, look for a number (only landlines in those days) or an address, and maybe follow up. The people around me became my tribe—my old tribe still somewhere in my affections but out of sight, and more than likely, out of my life.

As a group of friends, we made arrangements to meet, and met at that time and place. If you weren’t there, something had happened. Half an hour was the usual amount of time to wait before giving up. If we called each other, it was to make these arrangements or to cancel them—very occasionally to chat about a specific thing, or, in the case of love, to listen dewy-eyed to inanities and sweet nothings.

Letters were still sent. Then came fax machines. The boyfriend I was with back then had an Apple Mac desktop computer on which he played endless games of Crystal Quest. The screen saver was a fish tank with the occasional flying toaster criss-crossing the screen. I would use the word processor to write proposals and requests for our never-to-actually-happen adventures to Africa, which we’d print out and send through the post.

Until the advent of the fax. The joy of feeding a letter into a machine and having someone pick it up almost instantaneously at the other end was immeasurable. It was sci-fi at home. It was how he and I communicated when he was away, and I wasn’t—long, complicated feelings spilled onto a page and then translated into, what? I don’t know how that worked, and even though I have the answer at my fingertips, I simply don’t care enough to tippy tap it.

For a while, that was it with technology, as far as I knew. I had a baby, and the only technology I was interested in was how to make it pain-free, despite opting for an all-natural, woo-woo-style birth.

I was pretty broke in those days, and although I understood the system well enough to get the help I needed from HM Government, there were no frills. I had a buggy—the folding umbrella kind—with which we would sally forth, a spare nappy in one pocket, and age-appropriate snacks or bottles in the other. That was pretty much it. Now? Cameras in their bedrooms, giant bouncy buggies that double as entertainment centers, and where that fails, they get handed a phone to play with.

I know what that sounds like—sniffy, middle-class judgment. Perhaps if I had been a perfect parent to a perfect child, I could have some grounds for saying my way was the right way. But we were neither, and other ways didn’t present themselves. It’s just how we were, and I didn’t need any tech other than a decent folding buggy.

Before the internet came into our homes, endless questions from the small boy—the hows, whys, and whats—would most often be answered with, “I don’t know, let’s look it up when we get home,” which we did—first in books and then on CD-ROMs. Then, slowly, after the Dell arrived, along with the internet, we began to ‘google’ things. It was clunky in those days, even to those of us still in awe of such possibilities. But he, like all kids of his generation, was the fertile soil for the technological seeds being scattered without any of us realizing it. I was too.

A PlayStation also arrived in our home, a gift from the small boy’s dad, on which they would spend hours playing a downhill skiing game. Any niggling doubts about the benefits of this screen time, which wasn’t even a concept back then, were shunted aside—it was part of their time together, after all. Then a Game Boy appeared—fantastic for car journeys, I thought.

I fell in love again around the same time I got my first mobile phone. It was a Nokia. All texts were in capitals because I didn’t know how to change it. Beeps in the night as we exchanged nonsense. Until very recently, his name was still in my contacts, still in capital letters.

I’m sure no one wants a list of all my phones or how, when, or why my son got his first one too. It just happened. You think it will make things feel safer, until one afternoon they don’t answer, and it feels like you’ve been punched in the stomach.

Life without the internet feels, from this distance, like a safer place. There was scary stuff out there in my childhood, of course, some of which I knew about, but I didn’t need to know it all.

As I grew up, I watched the news and read newspapers, so I had information to hand when I wanted to look and had the headspace to absorb it, or indeed ignore it, if I chose. I read books—novels mostly—and learned about history and other cultures that way. I followed lines of thought if I was interested enough and studied them. I chose what to see, how to see it, and when it was difficult or sad or anger-inducing, I could look away and come back to it when I had some idea of what I could do with it.

I looked around my locality, communicated with people nearby, and with others by telephone or letter. I wasn’t bombarded or saturated with information, images, and videos. I didn’t have to field it all, as you do when scrolling through Instagram—one minute watching a cookery demo, the next witnessing someone being shot dead, followed by a cat video.

And this is where we are. Where do we go from here? Over to you Ash.

Thanks, Lizzy! I will share my side of the story in the coming days.

If you have reached this far then I hope it means you like what I’m doing and if so you might consider supporting me by ‘buying me a coffee’ ( Substack does not let me monetize my articles because I am based in India) which is a one off payment rather than a continuous subscription. Payments, however small, encourage me in my writing and mean that I can spend more time honing my skills.

You can buy my book which is a memoir about my 1800 km walk through India through my website. Thankyou, really!

There is one more thing by the way.

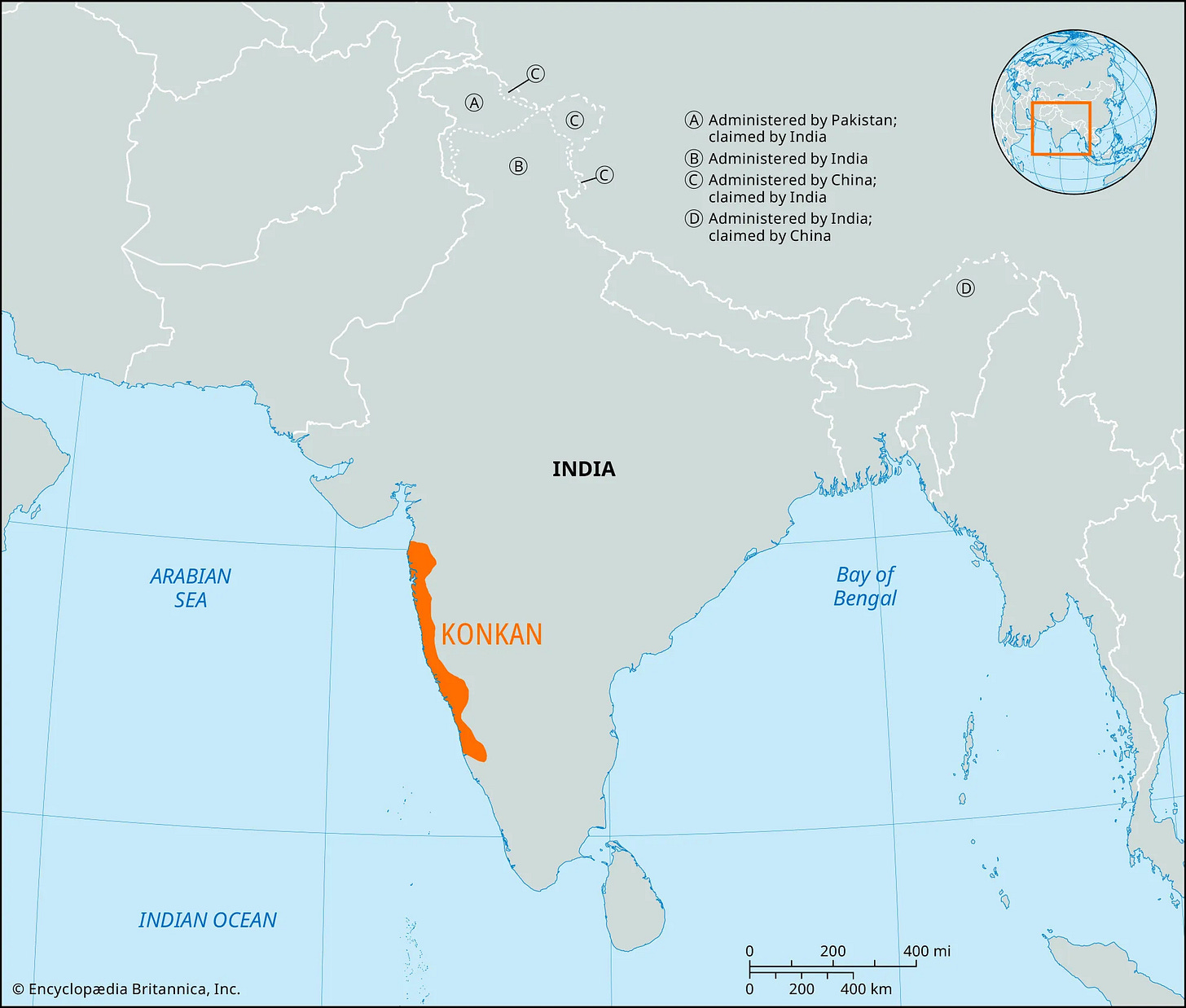

Most of you joined this Substack after reading stories from Saving a Village. In that series, I spoke about the urgency of taking action against the looming threats of deforestation, coastal highway projects, and the chemical and oil factories set to rise in this eco-sensitive zone. These developments could devastate many villages, including mine. That’s why I’ve decided to embark on a 500-kilometer journey across this stretch of land.

My purpose isn’t political, nor am I here to point fingers at specific companies or factories. Instead, I want to visit each village, sharing the message that while change is inevitable, it’s vital that we steer it in the right direction. I have no desire to cast myself as a hero; my goal is simply to witness this land and its fading culture before it's too late. However, if I can raise awareness and ignite even a small spark of understanding, I’ll be content knowing I did what I could.

But I can't do this alone. To plan the walk and cover necessary supplies, I need your support. Unfortunately, platforms like Kickstarter and other crowdfunding sites aren't available to me here in India, so I’m relying on your donations. You can contribute through PayPal—here’s the link. For donations over $30, I’d love to send you a personalized postcard as a token of gratitude.

I’ll delve deeper into this journey in the upcoming newsletters. Thank you for your support!