In 2022 I left off on a walk across India. The primary motivation for embarking on this journey was to document the farming crisis. At that time, the country had experienced a series of protests and demonstrations by farmers, particularly from Punjab, who had blockaded the roads leading to the capital, Delhi, over a bill that the government had introduced. Over the previous decade, there have been numerous farmer suicides and a pervasive sense of uncertainty and despair within the farming community. Despite these challenges, the government's responses had failed to alleviate the situation.

The government had taken a heavy-handed approach to suppress the protests, raising concerns about the right to protest and freedom of expression. I was observing these events from a distance while I was in England, in the final stages of completing my degree. The scale and intensity of these protests marked an unprecedented moment in Indian history.

The farming crisis in India has been a long-standing issue with significant socio-economic implications. India has witnessed one of the highest rates of farmer suicides globally. The National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) reported that over 296,000 farmers and agricultural laborers have died by suicide between 1995 and 2015. The reasons behind these suicides include debt burdens, crop failures, and lack of access to credit and support systems. The average income of Indian farmers is considerably lower than that of non-farmers. According to data from the National Sample Survey (NSS), the average monthly income of a farming household in rural India is less than half of that for non-farming households. This income inequality exacerbates poverty in rural areas. Approximately 58% of India's population is dependent on agriculture for their livelihood. However, the agriculture sector contributes only about 15% of India's Gross Domestic Product (GDP). This imbalance indicates that a significant portion of the population is engaged in a sector with limited economic returns.

Landholdings in India are often small and fragmented, which makes it difficult for farmers to adopt modern agricultural practices and technologies. Small land sizes result in lower crop yields and contribute to the agrarian crisis. A substantial portion of India's agriculture is rain-fed, which means it heavily relies on monsoon rains. Insufficient irrigation facilities lead to crop failures during droughts and an overdependence on erratic weather patterns. Many Indian farmers find themselves trapped in a cycle of debt due to high-interest rates on loans. When crops fail or prices drop, farmers struggle to repay their loans, often resorting to extreme measures like suicide. Government policies, particularly in the procurement and pricing of crops, have often failed to provide adequate support to farmers. Minimum support prices (MSPs) set by the government sometimes do not cover the cost of production. The agrarian crisis has led to significant rural-to-urban migration as farming becomes increasingly unsustainable. This influx of labour into urban areas has placed pressure on urban infrastructure and services. Frequent instances of crop failures due to climate change, pests, and diseases have added to the woes of Indian farmers. Unpredictable weather patterns can lead to significant financial losses. These and many other problems grapple the modern Indian farmer.

Farmers are often considered the backbone of any nation, and the smooth functioning of a country depends on the well-being of its farmers. Throughout human civilization, nations have relied heavily on agriculture. The Indus Valley Civilization, for example, thrived along the banks of the Indus River, primarily sustained by farming. Tools designed for farming have been integral to human progress, from the earliest days of hunting to the advent of agriculture.

While Western nations have developed highly advanced farming machinery, India remains heavily reliant on manual labour in agriculture. The project I was working on aimed to document this crisis, but I was also eager to witness the glimpses of a vanishing, traditional India.

The farming crisis is more profound and destructive than what is typically portrayed. The mainstream media often attributes it to factors like droughts and excessive rainfall. In my observation, the crisis primarily stems from the degradation of the quality of farmland and land ownership. The impending crisis is about small-scale farmers losing their lands at an alarming rate, often due to government support for private industries. Government policies and officials play a significant role in this process, and I will elaborate on why I believe so.

Let's begin with the case of seeds and fertilisers. Khandogi, a local farmer, told me that in the recent past, he used native crop seeds that yielded better results and had superior nutritional value. He relied on organic manure, composted soil, and dried grass for natural fertilisation, which was not only cost-effective but also environmentally friendly. However, the government's attempt to modernise Indian agriculture led to the introduction of seeds produced by foreign companies focused solely on profit. These companies have a virtual monopoly on the Indian seed market. At one point, Monsanto, a U.S.-based company, had complete control over the cotton seed market. The primary objective of these companies is not necessarily to provide better crops but to promote crops that require supplementary fertilisers, which is where their profits lie.

“Journey to the East” is now available on Kindle globally.

Have you ever wondered how the British managed to get the entire Indian population hooked on tea? Surprisingly, they began by giving it away for free. It didn't take long for people to acquire a taste for it, and now, centuries later, you can find tea in almost every Indian household.

In a similar fashion, the Indian state and its local governments subsidised foreign-manufactured seeds, which initially grew in popularity. Indian peasants eagerly accepted subsidised, and often free, seeds from local distribution shops. Little did they know, they were becoming unwitting addicts. It took time for them to realise that it wasn't they who were addicted but their land itself, addicted to these factory-manufactured seeds and chemicals.

Seeds produced by companies like Monsanto and others have significant financial interests in firms manufacturing fertilisers and other farming products. These seeds are engineered in such a way that they stand no chance of flourishing without supplementary chemical fertilisers. The average farmer is unwittingly drawn into a battle taking place in the towering offices of New York and London, a battle driven by shareholders who prioritise returns over innovation. Some farmers can't even properly pronounce the word "hybrid." As a result, they helplessly buy more and more fertilisers when their crops are undernourished. The cost of these fertilisers keeps increasing each year, and they often face droughts or unexpected weather patterns for which they are unprepared.

Typical Indian farmers select seeds they believe are suitable for relatively stable weather conditions. For example, many avoid sowing groundnut seeds out of fear that excess rain would drown their crops. Instead, they opt for the safer bet of planting sugarcane, which requires less maintenance.

However, what they often forget is that sugarcane consumes excessive amounts of water, leading to the alarming depletion of groundwater resources.

Now, let's delve into the world of sugar manufacturing plants. Most sugar mills are operated by ministers, ex-ministers, or their relatives, enabling them to dictate and manipulate the price at which farmers must sell their produce.

Consider the case of Ankush Pawar from Mayani. At the age of 35, he was a husband and father of two who chose to end his life by hanging from a ceiling fan. Ankush was a sugarcane farmer, cultivating what's considered a cash crop. Analysing his situation, Ankush owned his land, so it wasn't a case of land seizure by landlords. He had a small sugarcane plantation, which represented his sole source of income for the year. Ankush carried a loan of 3.5 lakhs from the local society, which he could have easily repaid if he had managed to harvest his sugarcane on time.

In rural India, an average farmer typically generates an annual surplus ranging from fifty thousand to one lakh rupees (500 to 1000 pounds a year), with most of this income being reinvested in their land.

Ankush's sugarcane crop was fully grown, and he was eagerly awaiting the green signal from the local sugar industry to harvest and send it to them. Typically, sugar manufacturers send a team of lower-caste contract workers to cut and transport the sugarcane to the factory. This cost is deducted directly from the farmer's account upon payment. However, in Ankush's case, there was only one sugar-producing facility in the vicinity, leaving him with no other choice but to send his produce there. Despite numerous visits and pleas, the management at the factory chose not to send workers to cut and transport the sugarcane. As a result, Ankush watched helplessly as his crop rotted in the field. Witnessing the destruction of a crop he had toiled so hard to cultivate was a heart-wrenching experience. It drained the life out of him.

Ankush chose to end his life rather than face the shame of not repaying his loan, or even worse, the prospect of going to jail. Sadly, Ankush's story is not unique. While not every suicide can be attributed directly to farming, it's evident that the lack of support, systemic corruption, and economic hardships contribute to anxiety, depression, and, in some cases, substance abuse and domestic violence.

While these issues were prevalent in many parts of Maharashtra, in the regions of Marathwada and Vidarbha, I stumbled upon a form of corruption that, in hindsight, may not be as unique as I once thought. The story I'm about to share is not just one isolated incident, but rather a recurring narrative found in many cases. It brings to mind the underappreciated movie, 'Peepli-LIVE'.

In this narrative, a man passes away due to various causes, whether it be hunger, alcoholism, or a heart attack. The specific cause of death doesn't matter to those who sit on governmental boards. What unfolds after his demise is the real story—a haunting reality in many parts of India. I must warn the soft-hearted; this is a narrative that's deeply troubling.

This, in my view, represents a new low in our human species. Following the death of a farmer, local politicians and government bodies spring into action. There is an opportunity hidden within this death. The Government of India provides compensation to the family of the suicide victim—an amount of 1 lakh Indian rupees. Out of this sum, nearly 75,000 rupees (750 pounds) are distributed through a convoluted scheme over a span of 5 years. However, the real shocker is the remaining 25,000 rupees (250 pounds), which are directly handed to the family.

In rural areas where the caste system still wields immense influence and the principles of democracy have yet to penetrate the masses, educating them about their rights can be a formidable challenge. It's here that government officials exploit the lack of education and the crude systems of oppression in place. Numerous instances have come to light where government officials have resorted to heinous acts.

In some cases, they have tied a deceased man to a rope, hanging him from a tree to fabricate a suicide. In others, rat poison has been injected into the body of the deceased, with a staged setup to make it appear as an authentic suicide. This represents a failure of the Indian State and its democratic principles, as these occurrences take place at the governmental level. The very individuals who are supposed to protect against such injustices are themselves implicated in many instances.

In saying that this occurs in India and that a substantial number of governmental bodies are corrupt and accept bribes, I'm merely stating an undeniable truth in this case. The only ones who would oppose my previous statement are those who are so upright and clean that they wouldn't find it offensive if I were to express these facts bluntly. You know who you are.

These villagers, many of whom have never seen that kind of money, often fall under the influence of these government officials and do as they are told. To be candid, it's often due to the fear of facing violence or being ostracised from their community. What follows after the deceased is labeled as a suicide? Those 25,000 rupees are then divided among the officials who handle the paperwork. A 'cut' is given to the local politician who wields power in the village. These 'cuts' are a common practice throughout the state. Most politicians receive significant sums of money from the government treasury, which should rightfully belong to the public. In the end, the widow of the deceased receives a mere 5,000 rupees, if she's fortunate. The bulk of this public money never sees the light of day.

So, what role do foreign-based companies play in this? Their primary aim is profit. It's their motto—to buy more yachts for the wealthy 1%ers. They are usually at their happiest when they find a government or a country that is corrupt. Such an environment is the perfect opportunity for business. Everyone profits from exploiting the Earth, and it's the common man who ultimately pays the price.

I struggle to ask this question. What we knew before colonisation, and what changed it all, is an immense datum of knowledge, guised as information. In many ways we are made to forget knowledge, so we turn ourselves in to the institutions that marvel themselves as the temples of wisdom, when in reality, they are an accumulation of pre-colonisational wisdom. This wisdom was free-flowing and all encompassing. It was a sort of wisdom that came without having to travel too far to reach it.

The primitive society holds some bits of that ancestral wisdom, in the form of memory. There would be no truth to it if these societies were long dead. When one indulges into the fields where these societies perform their dance for bread and butter, one simply comes to a realisation, that we have degraded, that we have fallen from a beautiful garden, to a rotting hell. In fact, traces of that garden are to be found all over. Primitive societies speak a language that encompasses all that is to be found around them. They are- it seems- almost instinctively aware of their surrounding flora and fauna. It seems paradoxical, how could education erode the primitive mind? ..but that seems to be the case. The importance that is given to a class of society that is progressing or first-world, and the negligence of modern education, which buries every other form of society into a thousand layered structure meant to disappear the individual cultures, is at its core disheartening. Science- the new religious science- seems to be performing a shameful act of homogenising the globe, where independent cultures-still very much alive in memory- are under the attack of larger powers which engulf these smaller cultures.

Food. The basic necessity that charges all human activity, seems to have lost itself into the warring bio-engineering giants. Talks with farmers all over India reiterate the same thing over and over, that food was available, and that the crop used in the olden days was more nutritious than the snicker bar that crowns the energy department today. All life revolves around energy. Our activities, since forever, have been a give and take of energy. Energy that was readily available for the ancestral man. One has to question the way in which bioengineering companies that sell the so-called patented crop, even create the natural seed. A natural substance, which was- again, readily available- was modified in such a way, that to have a crop, meant having supplementary fertiliser. Fertiliser, that ends up killing the potency of the otherwise nutrient-rich soil.

"Grandfather used to say, his grandfather only scattered the crop around and it would give glorious yield, without any added chemicals’, this is a common expression all around the country. How can it be that every farmer feels and has the same memory? This suggests a simple fact, somewhere in the past few decades/centuries, our responsibilities as a species, towards our own kin, have been misplaced. There even seems a possible hijack of the system, to mould and re-shape our knowledge of history and science, in order to cater to a specific colonial mindset, which negates everything and everyone other than itself. The colonial mind rejects every advancement achieved in the collective human past, so that it can be used and abused, only to present that same advancement as their own, authentic discovery.

To even speak of such a thing, is to invite a thousand arrows on one's bare breast. The objectives of Science seem to have devoured from its course. The river of inquiry is flowing dry, with a dam of madness obstructing its flow upstream. Concepts, that a city-dweller, well-versed with a particular close-minded, almost religious form of science thinks to have, are laid out only in the past centuries. A city-dweller is a modern slave, a slave to close-minded ideas that envelop a small land-mass in which he exists. This city-dweller thinks that it is his job to inform and educate every person who is 'primitive', and thus performs the act- which in essence -is no different than the one of missionaries. To spread freebies, torcher, shame and outright kill people who are against their idea of right and perfect. Science, is the new religion and education systems- schools, are the new churches, yet the ground of reason for this scientific conversion being the same as before- "fear".

Societies that have an extensive amount of this past wisdom, seem to be controlled by subsequent governing bodies that are more colonial in their approach, in the sense that they not only want people living inside their imaginary landmass, to be subservient to them, but they also want them to forget every part of their ancestral wisdom. The rapidity of change is almost disturbingly real to an outsider, who is watching this change from a sceptic window. The urgent need for this machine-like orb that wants to destroy every thought, which contains even a minute hint, 'that man was afterall a free-spirited being, who roamed around the garden, without ever having to pay any institutions, to merely exist'. It is telling that the people who run and administer these institutions have a lot to lose, mainly their comfort and standards of extravagant living. It is this excess that is destructive.

Predicting whether this situation will change is challenging. What I believe is that it's only likely to worsen. We lack visionary leaders, and the so-called visionary leaders often seem unable to step out of their palaces to witness the plight of the common citizen, let alone farmers and protestors. It's worth noting that only recently, a decision in India was reversed following a year-long farmer protest. During this time, India witnessed a surge in surveillance, mobile network bans, and the manipulation of news and social media to shape public opinion. In many cases, news outlets went so far as to demonise the protestors and praise the Almighty Lord who introduced these laws in the first place.

Each time someone dies, it becomes easier for the vultures in our society to feast on the leftovers.

The situation appears bleak and tragically familiar to anyone living in rural areas. It was one of the many reasons behind my decision to step away from the work I had initially set out to do—to document the farming crisis. Regrettably, this issue remains one of the least discussed pressing concerns, and a viable solution seems far from sight. While figures like Vandana Shiva have been doing commendable work in highlighting this issue globally, it still pales in comparison to the magnitude of the crisis we confront. It's a call for action.

The farming crisis in India isn't solely a product of climatic factors. It's a complex interplay of exploitation, corruption, and policy failures. Addressing this crisis demands a comprehensive approach. The government must make the welfare of farmers a top priority, fostering sustainable farming practices, equitable access to markets, and affordable technologies. The influence of profit-driven corporations should be tempered by transparent regulations that prioritise the well-being of farmers. In addition, media and public awareness campaigns can help bridge the gap between urban and rural India, nurturing empathy and a shared sense of responsibility.

Ultimately, the solution to the farming crisis necessitates a holistic reimagining of India's agricultural landscape. It calls for leadership that transcends profit motives and envisions a future where farmers not only survive but thrive. It is only through collective action, governmental accountability, and a renewed commitment to the backbone of the nation that India can steer away from impending catastrophe and toward a more equitable and sustainable agrarian future.

..but then when I am going through these thoughts, I am time and again reminded by these words from a friend.

“Everything changes. Very slowly, but it does. People change, slowly, but they do. Governments change, and you know what? They change much quicker than you'd think. All you can do is add your tiny little input so that the direction of the change is towards what you think is "right", but that's about it. Don't expect immediate results. Actually, don't expect any result at all. If you ever find yourself in a situation where you have to decide between "common good" and "your good", don't be afraid to choose the second option. Be selfish, not always, not mostly, not even regularly, but be - sometimes. Try your best to never slip into despair. I sometimes have a problem with this myself - fully realising this world is full of powerful corrupt people, full of irrational or ignorant people, full of incompetent people who are in charge. Still, that's the way it is and you cannot do anything about it. You can only choose to go crazy or not. I suggest the latter option…”

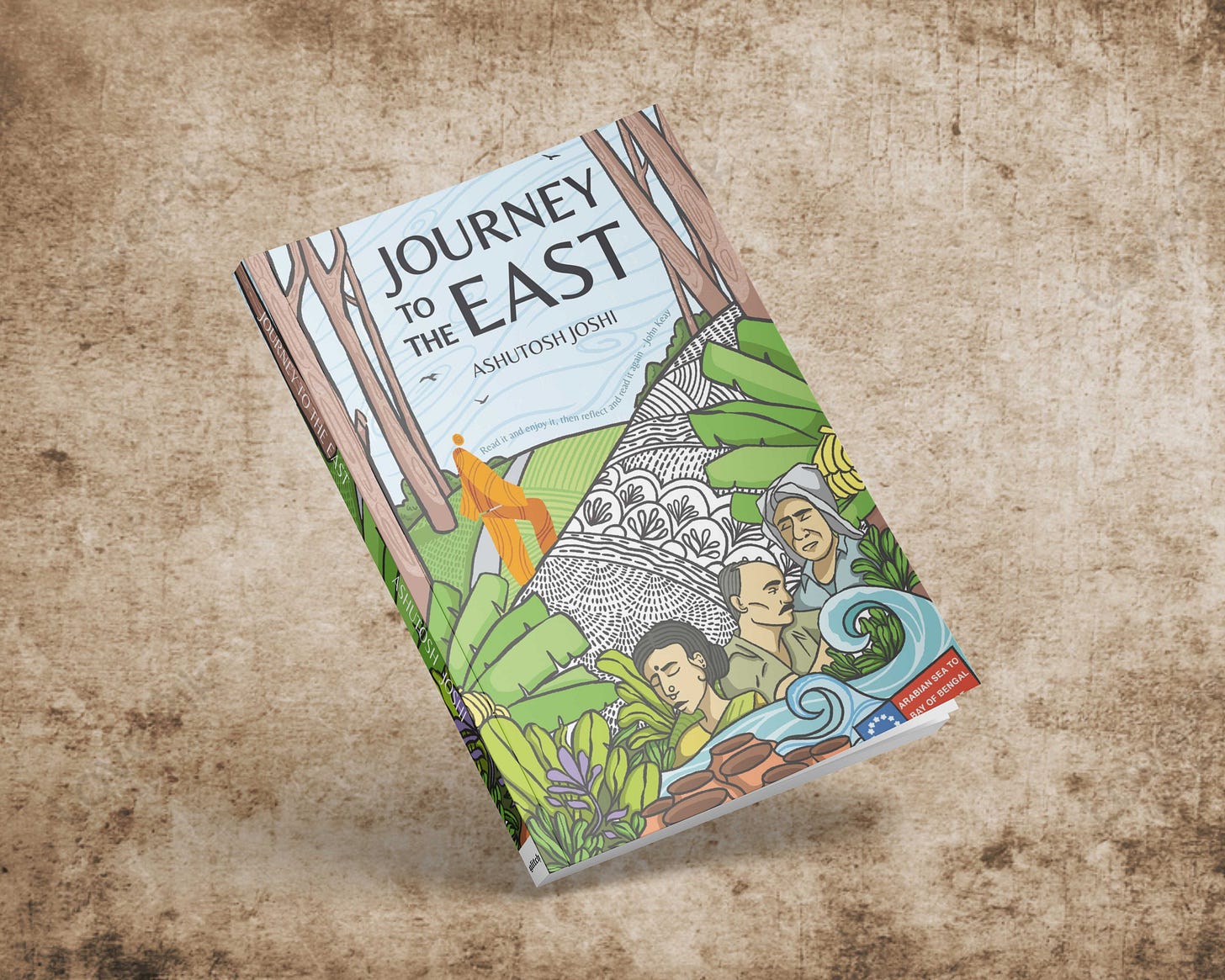

Thanks for reading. If you are still here, I would take this moment to direct your attention to a book I have written. This book is almost 2 years in the making. In 2022 I left off on a walk across India and ended up walking 1800 km from Narvan on the west shore, to Visakhapatnam on the east shore. Initially to document the issues plaguing rural India, the project unfolded to become an unforgettable voyage of self-discovery; involving sleeping in unfamiliar places, venturing alone through the Naxalite insurgent jungles, and even being interrogated in a jail cell.

After contemplating on what is the right way forward, I have come to the conclusion that I will self-publish it- and I did. If you are interested in reading about my journey and supporting me to become a full-time writer, please consider buying “Journey to the East”- which is currently available through my website. www.ashutoshjoshi.in

If you would like to help me out in other ways, you can buy me a coffee via paypal, www.paypal.me/ashutoshjoshistudio. You would think that a couple of dollars/pounds won’t mean much, but it does, especially in India where it is difficult to make ends meet as an artist.

You can buy my first book “Journey to the East”, a memoir about an 1800 km walk through India, through my website .

If you would like to buy prints of my photographs, you can choose the photographs you like on my website and send me an email. I will send you custom quotes for the sizes you’d like.

There is an American permaculture teacher, Andrew Millison, who has a YouTube channel that features amazing regenerative farming projects around the world. Many of them are in India.