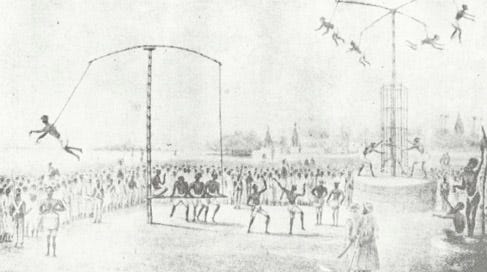

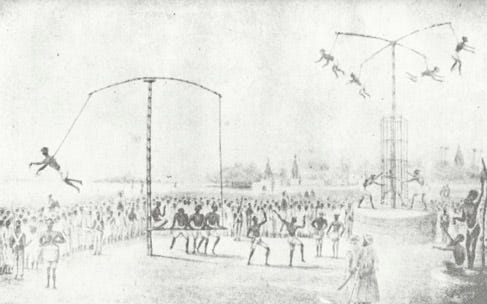

Imagine this: a cold, metal U-shaped hook is inserted into your back. You are led to a wooden frame, and the hook is interlocked into it. Now, strangers—people you don’t know and don’t trust—ask you to trust them with your life. They pull the wooden frame from the other end, suspending you mid-air. Hundreds of eyes are fixed on you, watching as you spin in circles, the hook stretching your skin, preventing you from plummeting to the ground.

No. This is not a dream. I know what you're thinking: ‘What a nightmarish situation!’ But what if I told you that people in my village, and a few others, do this deliberately? They do it with purpose and hope, each one wishing for something specific—a child, a healthy family, a better home. It’s more than a random event; it's a ritual. Thousands from surrounding villages come to witness this procession. Stalls are set up, toys and incense are sold, locals offer snacks and lemonade, creating a bustling micro-economy. In our hyper-modern world, this tradition has somehow retained its authenticity.

If you still don't know what it is, I welcome you to the annual procession called ‘Bagaad’.

The origins of this festival are shrouded in mystery, with no one knowing exactly when or how it began. Ask someone, and they might say, "It has been going on for eternity." Others, more grounded in local lore, might tell you, "It started when the goddess ‘Vyagrambhari’ first arrived in this village." Yet, one story stands out, a tale from the times of the British occupation of India, which elevated this festival to the stature it enjoys today. (More on that towards the end.)

If you search for stock photos of ‘Bagaad’ on Alamy.com, the caption reads, "Devotees get hooked and then hanged in the name of God." These photographs, taken by Westerners, misrepresent the event, and the caption reflects their limited understanding. But is that all there is to it? Are people merely getting hanged in the name of God? If you ask me, or any other villager who has witnessed this event since birth, we’d laugh at such a description. Like many other processions in India, this is not merely a religious act but rather a profound test of physical and mental willpower.

Now, there is a science to all this, just like there was science to some older pagan and Christian rituals. After all the generations who came before us weren’t fools hanging themselves in the name of God (and if we think that, we are highly misunderstanding their skills). The man (yes, there are usually men being hooked. Maybe it is also because men can keep their chest and back open in order to get hooked, which the women cannot due to societal obligations) fasts for almost a day and a half before getting this pointed metal thing in his back. This fasting helps the person with self-restraint, but it also has many other benefits here’s an article from Johns Hopkins Medicine.

Research shows that the intermittent fasting periods do more than burn fat. Mattson explains, “When changes occur with this metabolic switch, it affects the body and brain.”

It affects thinking and memory, heart health and improves physical performance. All these are vital for the one who chooses to get hooked to the bagaad.

Madhav, the only vegetable vendor, who is otherwise an ordinary figure, gets the attention of the entire village. You would otherwise see him weaving baskets, handing out tomatoes and walking barefoot in a men’s tank top throughout the village market, but during this festival, he becomes famous and understandably so. This is the 16th continuous year when he getting ‘hanged’. This is the only day when you see him all dressed up - without a tank top - waiting for his turn. I asked him what makes him do that, to which he replied, ‘I think I feel a sense of connection with the world. It is almost like you are forgetting yourself when you are up there. You get a bird’s eye view of the world. It gets you ready for your life.’

I have very little self-restraint to judge him. Plus, I know that he is not lying, because he is the only man in the market who always has a perpetual smile on his face - always excited about the day. Even when there are no customers, you can see him chatting with people waiting for their bus at the next shop. He's always engaged in work, and perhaps this self-restraint during ‘Bagaad’ has something to do with it.

It's important to note that not everything in this festival is solely the doing of God. Like many religions that began as a means for man to understand his own nature, only to become fragmented over time, so too has this festival evolved. Many have become blind believers, to the point of paying others to endure the pain on their behalf. Those who now live in urban areas, with enough wealth to fulfill their wishes without undergoing such trials, often bypass the experience entirely.

May all that have life be delivered from suffering.

Gautama Buddha

A ‘mhorkya’ -someone in their place - can get ‘hanged’ and ask God to fulfil their wish. This is not the true spirit of this sport. You cannot ask someone else to bath off your sins, you will have to do it yourself.

Pain in life is inevitable but suffering is not. Pain is what the world does to you, suffering is what you do to yourself [by the way you think about the 'pain' you receive]. Pain is inevitable, suffering is optional. [You can always be grateful that the pain is not worse in quality, quantity, frequency, duration, etc]

Gautama Buddha

There is a famous story during the times of Buddha. In the Angulimala Sutta scriptures, Buddha turned a blood-thirsty murderer, Angumila, into a saint and later into an enlightened being, but what if that man had asked someone else to get enlightened in his place? That is the same case with this festival. You have to show immense patience, self-restraint and courage to do the undoable, to tweak reality according to your will. This is more than accepting suffering, it is to gain control over your mind. That is the essence of this, not the thousands of spectators, not the heroism, not even the God, but self-knowledge. That is the key.

Now, let me share the British story. When the British arrived and became the rulers of India, they encountered this festival, which was prevalent across India and Bangladesh. Misunderstanding its significance, they deemed it a practice involving divination and malefic magic and decided it had to be banned. The British, coming from a background where women were burned for witchcraft and scientists and alchemists for heresy, saw 'Bagaad' as similarly unlawful. They moved to stop it.

From here, the tale turns into folklore, known by almost everyone in the village and surrounding areas. One day, a couple of British officers, while patrolling, decided to visit this so-called 'Bagaad.' Villagers were protesting, pleading with the officers to let the yearly procession continue. In India, festivals are continuous affairs; stopping one could anger the gods, causing dire consequences. For example, you cannot stop bringing an idol of Ganesha in your house unless something extremely bad happens - like someone in your family dies.

The villagers kept pleading, but the officers remained defiant. One day, while visiting, the officers made themselves comfortable in a house. Suddenly, two leopards entered the front yard. The officers asked for help, but the villagers insisted it was a bad omen, a sign that the gods were displeased with their decision. "Let the procession continue, and the leopards will do you no harm," they said. After hours of defiance, the officers finally relented. The leopards left soon after the officers agreed to the villagers' request.

Word spread quickly about what had happened, drawing hordes of people to witness the procession. Thus, a festival that was typically undertaken by tribal people gained the stature it enjoys today. People from near and far come to see the ‘hanging man,’ but for us, it's just our friendly neighbor Madhav, embracing the challenge, learning patience, self-restraint, and conquering suffering.

fun fact- there’s no blood being shed from the shed and there hasn’t been even a single case of death in all these years. I guess older generations were much more experimental with their body and their mind. We have just grown pale in comparison. Maybe we simply gave that dignity and freedom to the hands of the government and corporations.

Are there any such festivals that happened in your place which have now diminished?

I am sure that there is a lot of history about the world and its cultures that we do not know and sadly we have lost some of that to the changing times. But, I would like to know what such events happened in Alaska or Norway or France or wherever you are reading this…

If you would like to support my writing, you can buy me a “coffee” (it somehow feels strange, knowing that you have an idea about my coffee drinking habits)

via paypal, www.paypal.me/ashutoshjoshistudio.

“Journey to the East”- is currently available as a paperback through my website and on Amazon Kindle globally. www.ashutoshjoshi.in

Ashutosh--Thank you for writing about this ceremony. May I ask what benefit such extreme asceticism brings that cannot be found more easily on the “Middle Way”? For example, you bring up intermittent fasting. This seems more practical for everyone and very reasonable compared to the extremes of primal culture ascetics, such as those that hook themselves, whether in India or America (A Man Called Horse). What is the ultimate goal?

I once met a man once, from India, who taught meditation. Devotees asked him if he went deep in meditation and travelled with his astral body to India. He said, “No, I take Air India.” They asked if he used special breathing techniques and mental focus to heat up his body when cold. He said, “No, I put on a sweater!”

Ultimately, of what benefit would the extreme bring any of us that cannot be found on the Middle Way?

Again, thank you for writing about this festival!

Looks very like an initiation ritual practiced by the plains Indians in America (Sioux, Cheyenne etc) for young men becoming warriors. It featured in the film A Man called Horse, only they used lots of hooks, not just one.