The ghost of the British East India Company is still haunting us in 2025!

Konkan the new Berar of India

Yesterday, I had the honor of speaking at an event in Nagpur, the orange capital of India, during the annual "Seed Festival." The festival was born out of the growing concerns about the health of the average Indian, which has been deteriorating due to poor agricultural practices. A group of individuals working in the organic farming sector, many of whom collaborate with local farmers, came together to establish this festival with one purpose in mind: to spark a conversation around issues that matter. Over the years, the festival has steadily gained traction, drawing more and more attendees every year.

People from all over India gathered, representing their local seed networks. These pioneers of the organic movement, many of whom are often seen as "eccentric" or "mad," began saving traditional, indigenous seeds and creating seed banks to ensure their preservation. This was a time when most people were turning to genetically modified (GMO) or hybrid seeds and chemical fertilizers, seeking quick yields, but neglecting the long-term health of the soil and the food chain. The fertilizers and pesticides that were used to grow these hybrid crops were creating a future filled with environmental destruction. India was swept up in the Green Revolution, pushing for increased crop yields at any cost. People were hungry, and their bellies were filled, but with food that was part of a much larger crisis, one that few recognized at the time. But why did hunger become so widespread in the first place?

It’s a crucial question. The British colonial period in India is well-documented, and we know how the colonial powers profited from a starving Indian population. The Great Famine of Bengal, one of the most horrific chapters in the history of British rule, was discussed in recent years at Oxford University by Indian MP and renowned author Shashi Tharoor. The infamous remark by Winston Churchill during the famine, "Why hasn’t Gandhi died yet?" is a stark reflection of the callousness of the British towards the suffering of millions. The East India Company extracted vast resources from India, including its agricultural wealth, but at a terrible cost to the local population. But were the Indian farmers and their land really as impoverished as we perceive them today? Can we be sure that we aren't repeating the same mistakes that led to the tragedy of the colonial era?

Just before I was invited on the floor, Gurudas Nulkar, a prominent academic, spoke of how the Indian palette has changed in the recent decades. My speech was followed by a book review of Ecology, Colonialism and Cattle : Central India in the Nineteenth Century, by the prominent author, researcher, Laxman D. Satya. The topic of this book, although faded in the pages of the past, offers a new insight into the current suicides in the Vidarbha section of Maharashtra. You see, my first walk was to document this farming crisis in India, where even today seven people (on an average) commit suicide each day. Wait. You must be thinking, but Ash, how does what happened in the 1860’s corelate to the suicides of today? …and moreover how is the government of today repeating the same old mistakes? Haven’t we come a long way from colonialism?

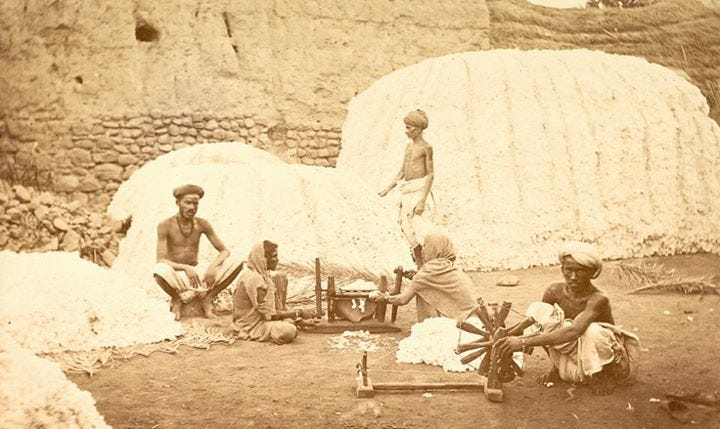

I, too, had these same questions. But the book review opened my eyes to a powerful connection. In the 19th century, the British East India Company leased land in Berar (now Vidarbha) from the Nizams. Following the Indian Rebellion of 1857, the British Crown sought to maximize profits from India. Researchers discovered that the fertile black soil in Berar was perfect for growing cotton, and so a plan was put into motion to convert the land into a cotton-producing zone.

Was Berar a wasteland and drought-ridden as it is today? The British research paints a different picture. This region was rich in all aspects. It had many kinds of vegetation. The cattle here were famous all around India. Sure, it had unusual rain patterns, but that didn’t mean that they had no water. The Nizams and the earlier rulers had built many lakes and ponds to conserve water. This region had wetlands. It had open fields for cattle-grazing. These were the lands that the East India Company deemed as wastelands and thus started leasing the land further to the farmers, the catch being, they had to grow cotton and sell it to them. That sounded like a fair deal back then. You were getting protection from the British throne. But little did anyone know that this flattening of wetlands and grazing patches would eventually lead to the first recorded suicide in the year 1870. Now, why did this happen?

You can buy me a coffee via paypal, www.paypal.me/ashutoshjoshistudio

Nature is a giving force. It expects humans to co-exist. The natives knew this quite well and thus they co-existed with the surrounding nature, sparing wetlands and grazing patches which actually stored water for the years to come. Because the British had no taste in the land, but only in the monetary benefits of the cash crop it provided, this land started becoming infertile. In just ten years of clearing up large patches of land for cotton farming, Berar was going through its first recorded famine. A letter was sent out to the British High Commission to urgently look into this matter, to which the reply was, and I am paraphrasing here, “ We cannot make changes to accommodate the water tables. The cotton needs dry, black soil to get a crisp texture. This crisp texture sells in the market.” Thus an entire populace was left to die because the British corporates wanted a crisper cotton that only grew in a dry, arid soil.

Okay. Compare this with what is happening in Konkan. The story of flattening of the wetlands and grazing patches of Berar, is extremely similar to its Konkani counterpart— the sada (the rocky outcrop ecosystem). Here too the natives had left the table top piece of basalt and laterite as grazing patches and natural storage tanks during the monsoon. The sada in basically like a sponge. It soaks in all the water, keeps it in its womb during the monsoon and releases it during the winter and summer seasons. It is able to do so because of the infinite cracks and holes within its structure itself. The water seeps in through these holes and percolates steadily towards the tiny rivulets and underground springs— which in turn fills up the wells and perennial streams that flow through its jungles. We, the natives, know very well how important this sada is.

The natives of this land have used this rocky ecosystem to graze their cattle and grow their food. They have kept them as it is, not flattening it out or crushing the rock to make a levelled field. They know the importance of its contour. Its gradual slopes help the rainwater to pass through towards the sea while percolating the water in its womb. Unfortunately the ghost of the East India Company has come back to haunt us. And like East India Company had its middlemen, the current government too has its middle men— the local ministers. This government, which is making rules for Konkan, has no local researchers in its team. The research put forth by Madhav Gadgil, who won the UNEP Champions of the Earth award for 2024, was tossed aside of this regime. A softer version of this report, which gave mining and forest felling clearances, was adopted. And yet, even this softer version of the Gadgil report is not taken seriously by this government. The inevitable concretisation of the sadas, will not only disturb the water storage built by nature, but it will destroy it completely. The flattening of laterite and basalt to build numerous housing, petrochemical and industrial projects by the ministers sons and corporates like Adani, will bring us to an era of 1870’s. Unfortunately, the ones making these rules and building such projects, don’t even stay here. They are off to their golden retreats, in their private helicopters, when the ship hits the bottom, but where will the natives of this land flee to?

Just as the East India Company’s policies led to widespread suffering and the first recorded suicides in Berar, the government’s current policies may soon lead to a similar fate in Konkan. Crops are already failing—mangoes are no longer fruiting, cashew trees are withering, and groundwater is rapidly depleting. As rural populations migrate to urban centers in search of better opportunities, the fabric of local communities is being torn apart. The lesson is clear: we cannot eat cotton when we are hungry, and we cannot drink petrol when we are thirsty.

If we do not learn from the past, we may find ourselves repeating the same mistakes, with devastating consequences for our environment, our farmers, and our future. The British have gone but the colonial mindset that they left here is still making decisions for modern India..

If you are still here, I would take this moment to direct your attention to a book I have written. This book is almost 2 years in the making. In 2022 I left off on a walk across India and ended up walking 1800 km from Narvan on the west shore, to Visakhapatnam on the east shore. Initially to document the issues plaguing rural India, the project unfolded to become an unforgettable voyage of self-discovery; involving sleeping in unfamiliar places, venturing alone through the Naxalite insurgent jungles, and even being interrogated in a jail cell.

If you are interested in reading about my journey and supporting me, please consider buying “Journey to the East”- which is currently available through my website. www.ashutoshjoshi.in

For Indian readers, you can buy this through Amazon India. Here’s the link!

To support me in this journey, share a coffee with me via paypal, www.paypal.me/ashutoshjoshistudio

This discussion reminds me of James C. Scott’s Seeing Like A State, where bureaucratic governance required making entire territories and populations “legible“ to what was believed to be scientific administration. The intentions may have been benign in many cases, but the effect was to destroy evolved orders that existed locally, and then had developed overtime and which respected the conditions that nature provided. The people who lived under these conditions were often unable to articulate why they did the things they did in a way that was legible and “scientific” and therefore satisfactory to both public and private sector bureaucrats. Therefore, all of that inherited practical wisdom was dismissed as primitive and backward. The result was often catastrophic.