Rise up against the tides

Reclaiming our shores - Part two of Oil Spills on our shore #2

Thanks for being a continual support. Substack and most importantly all of you have turned out to be extremely kind and compassionate. I can be free and write my unfiltered thoughts, thanks to you. Your donations and occasional coffee help me keep going. I appreciate it from the bottom of my heart. Now that I am going back on a walk this year end, your contributions are helping me to manage the logistics for that walk. I know I cannot thank each and every one of you but I would like to thank Heather for being the first person to contribute for my upcoming project.

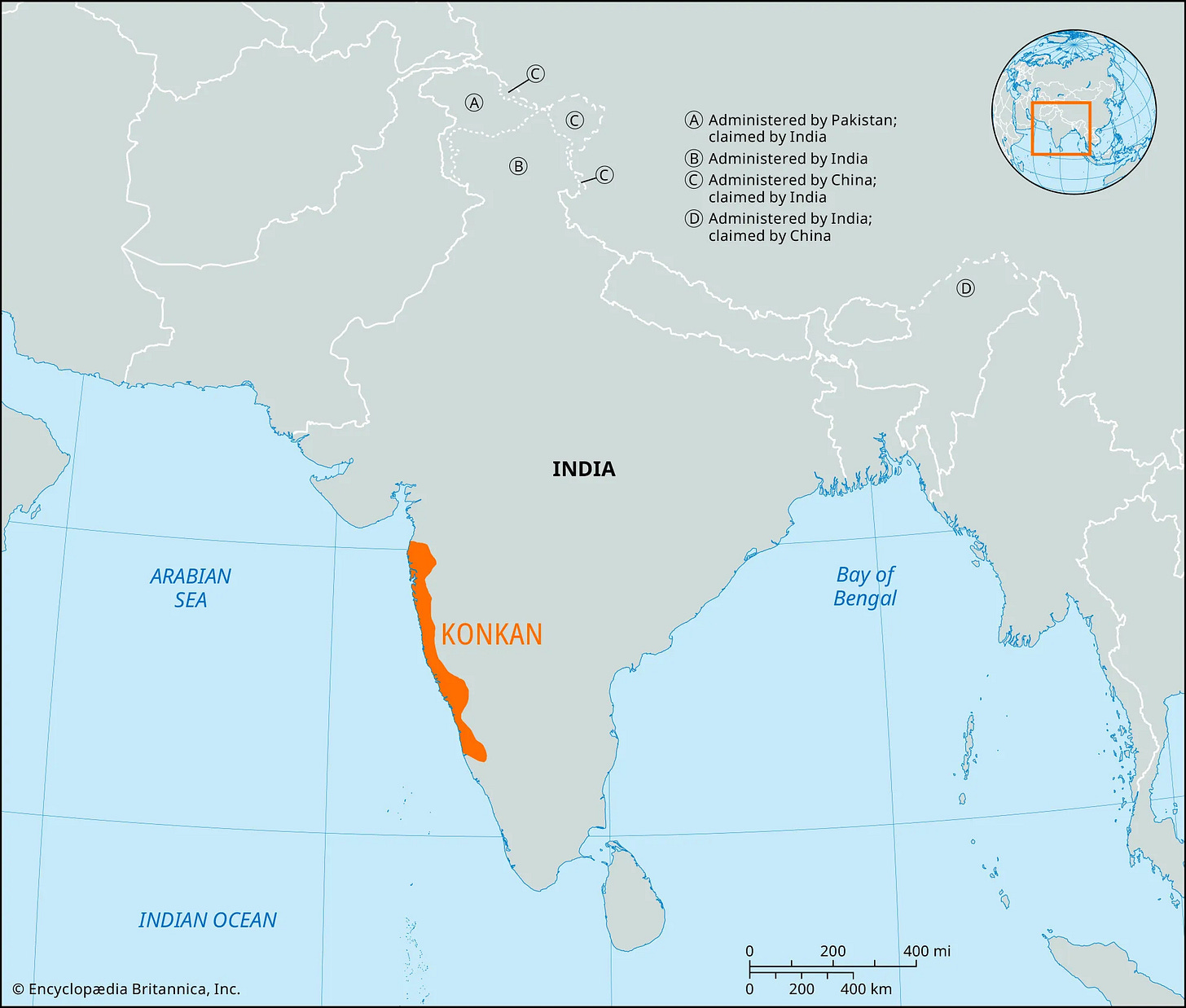

Kokan was always lush. Sandwiched between Sahyadri Mountain range and the Arabian Sea, Kokan often looks like a green rug which was spread around by God to enjoy her creation. I imagine her sitting in a resting chair amidst all the coconut and betel-nut trees, sipping tender coconut water while she enjoys the salty breeze that the sea brings. She must have liked it so much that she invited all of us to live here.

You’re not reading about oil spills on our shores—this is the story of how we, a small coastal community, came together to fight the pollution that has plagued us for years. While the world’s wealthiest nations discuss ambitious goals like net-zero emissions, we struggle to even look at our beach without despair. I won’t compare our shores to the pristine beaches of the Mediterranean, but that doesn’t mean our beaches were always this dirty and polluted. This isn’t a story of climate change alone; it’s a tale of human-made negligence and greed.

In India, laws may be carved in stone, but they’re often treated like sand—easily shifted, easily ignored. Every minister, every politician, no matter their rank, can be bribed. Even the police have their price for looking the other way. Lawyers? They fight for their earnings, even if it means siding with the unjust. It’s never an honest buck. Environment agencies are little more than factories churning out paperwork, none of which ever sees the light of day. Their ‘unpaid’ interns are confined to urban offices, far removed from the ground they’re supposed to protect. And our Chief Minister? He needs a red carpet to step from his car onto the polluted soil. Great efforts are made to keep those photos out of the news when they inevitably leak. It’s a farce beyond humor.

If you want to see what true apathy looks like, come to my beloved Konkan. It feels as though most of the people have already surrendered. "Son, they’re too powerful. What can we even do?" a local elder reminded me.

And yet, when I reached out for help, those same locals came together. Despite their weariness, despite their doubts, they stood by me when I needed them most.

We may not have the most famous beach, but we certainly had the most peaceful one. Before the shipping industries encroached, our evenings were spent in tranquil strolls along the shore. A narrow road beside the bridge—originally built to prevent the salty sea from overflowing into the land—wound its way to the sea’s embrace. Later, a rough road of laterite stone was laid for cars and heavy vehicles, a pathway born of greed for illegal sand mining. On the right, coconut groves whispered in the breeze, leading to a humble ‘bhandari’ settlement. Further along, the road splits—left to the soft sands of the beach, right to an ancient path threading through the jungle to the graveyard and finally, to the shore. The forest, now guarding the village, was planted in the 1950s and '60s by the hands of the villagers, aided by the Department of Forest, to halt the advancing sea.

Each morning, I find solace in this journey—walking through the forest, past the graves of those who came before, until I greet the dawn at the beach. In this single walk, I embrace nature, honor the departed, and welcome the new day. Yet, it grows increasingly difficult to witness the beach in its original, unspoiled form. Plastic waste now litters the shore, and oil spills and dead sea life wash up more often than I care to admit. Each time I walk along the sand, I feel the urge to act, to reclaim the purity of this sacred space. But life, with its relentless demands, always seems to hold me back.

This time, though, I made a resolution. It was October—the heat oppressive—but I found it to be the perfect moment to begin a beach cleanup. I had talked about it for months, using the monsoon as an excuse to delay. But now, the rains had passed, and it was time. I spoke with the villagers during the monsoon; all agreed it was necessary, yet they doubted anyone would join. “Everyone has work to do,” they said, “and no one has time for your crazy idea. Maybe, if every community sent a representative, we could gather 15 or 20 people.”

Deep down, though, I knew this cleanup wasn’t just for the village or the villagers. It was for me. In my selfishness, I admit, I needed to cleanse this beach. I am the only one who walks here daily, not for work, but for leisure. The others—fishermen and the illegal sand miners—don’t see the beach the way I do. I sit in the sand for hours, watching the waves, my dearest companions. But to sit on a polluted beach, surrounded by man-made waste, pains me. It is an eyesore, especially for someone who sees this place as sacred. And so, this cleanup is for me—so I can walk these shores in peace once more.

One October morning, I declared to my granny, "I'm starting the beach cleanup today."

Like any typical granny, her first reaction was, "Oh, sure you are!" with a sarcastic smirk.

Then she added, "Stay home. Do it in December if you must. Are you mad to go out in this scorching heat?"

One thing I've learned—often the hard way—is that when your will is strong, nothing, not even your granny's stern warnings, can stop you. It took me a while to realize that her words were more out of concern than prohibition. Once she saw my determination, her mood softened. She began preparing some light snacks for me, and from the old great-grandma's cupboard, she pulled out a hat—one that would shield me from the relentless afternoon sun.

By 9:30 that morning, I was off. I had sent a message in the village WhatsApp group, sharing the location and time of the cleanup. But I didn't expect anyone to join me; in fact, I knew no one would. That day, it was just me, a few beach dogs, and the sand mafia who claimed the beach as their territory. The sand mafia, villagers like me, approached to discuss the waste problem. They picked up a few plastic bags before returning to their work. Of course, a leisurely beach wasn’t their concern; survival was their priority. That day, I began to understand—though only partially—that the sand mafias I had despised were simply people too. Bread and butter had led them here, and the work they did, though illegal, wasn’t easy. I even helped them push aside a heavy log when they needed a hand.

I started at the far right corner of the beach, picking up every piece of plastic in sight. I found everything: toothbrushes, toothpaste tubes, syringes, and medical equipment. Plastic cups and discarded ropes from ships. Many pieces of Styrofoam, likely used on the ships, had found their resting place on the beach. Fishnets and shipping debris were tangled in the mangroves, choking the life out of these fragile plants.

Mangroves are the lungs of this sensitive ecosystem. In the past they would stop debris from getting into the coconut farms. They were cared for dearly, but then the villagers turned against them and they were left alone to fight a downhill battle against the worst of pollutants - plastic and the newly built sea ports. Now they are retreating, making it possible for more and more plastic waste and ship debris to enter the coconut farms and the jungle. Rampant bund building, unsustainable aquaculture and industrial growth are severely damaging mangroves in the Konkan coast.

A report was formed in he 2010’s which described damage to 108 mangroves in the Lagvan–Kasari–Satkondi mangrove patch along the Jaigad creek after a one-kilometer long bund was constructed three decades ago. This lies just across our beach at Narvan. The mangrove mortality increased over the past one month after officials closed down most sluice gates, cutting off tidal water to the mangroves. The area is now close to Jindal thermal power plant and Chowgule Steamships port project. NASA images reveal thick mangrove cover in the area in 1989, which has dwindled over the past two decades to a meager 35 hectares.

"The purpose of the bund is not clear and there have been different information with different groups in the villages. However, it was reported that the industries (JSW and Chowgule steamships) intend to store fresh water within the enclosed area. There are complaints from villagers that these activities are causing drying up of the wells in the vicinity, and thus there is strong opposition of the villagers to the whole plan," the report said.

Obviously, this report was published in 2010’s. We are far beyond the deadline. In 2024, these companies are way too powerful and they have a grip over the local politicians, spending unfathomable amounts of money to keep their greedy ships running.

The day drifted by as the sun dipped toward the horizon. I watched the sun appear to shift places—or perhaps I was simply witnessing myself moving along with the earth beneath my feet. Whatever the case, it was an extraordinarily simple day, marked by the monotony of the task at hand. I would choose an area, bend down, and keep picking up waste until that spot was clear.

There is a certain rhythm in monotonous work, a discipline that allows you to move through it with ease. In such moments, time seems to dissolve. The waves rolling in and out, and the clouds shifting in their dance, are the only signs that change is happening. Time, in this sense, is nothing more than change. If I spend enough moments watching the tides and clouds while picking up plastic, this beach will be clean someday. For me, this was also an escape—a reprieve from the world of technology and the internet. Here, with nature, I didn't have to worry about what others thought or said about me.

As evening approached, I noticed an old lady walking along the beach in the distance. Even from afar, I recognized her—it was my grandma. She had walked all the way from home to check on her grandson. A smile lit up her face when she saw me. I had only managed to clean 0.1% of the beach, barely a fraction, yet she was happy that I had begun. Sometimes, all that matters is the start. As they say, "A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step." How true that is!

Grandma and I sat on the sand, perhaps for the first time in a decade. So many moons had passed that we had forgotten, amidst life's chaos, how all we needed was an evening by the sea. We reminisced about my childhood—how I loved playing in the tidal pools, swimming in the then-clean sea, and how she would prepare a hot bucket of water for me afterward. I would be covered in sand, itching all over, but the excitement on my face never dimmed. When I left to study, those beach visits ended for Grandma. "What would I do, coming to the beach alone?" she asked.

That one small step I took that day proved to be a turning point, not just for me, but for the entire village. If one boy could work alone and clean 0.1% of the beach, imagine what 10, 50, or 100 people could do! More hands mean more progress.

The very next day, word of the cleanup spread through the village like wildfire. Every WhatsApp group buzzed with the news. The village sarpanch called me, eager to join. And so, from one, we became 30 by the weekend, making the work faster and more efficient.

But more on that in part #3

This isn’t just my story. Don’t be misled by how much I talk about myself here—I was merely a catalyst. Without the villagers, I would have gathered only a handful of waste from the shore. It was the community's collective effort that made this endeavor successful. It made me realize the power we hold when we come together. If we unite, we can face almost any challenge. In this digital age, we've grown apart, but perhaps returning to the community is the only way forward. This was my way of bringing us together. The youtube video (turn on CC for English captions).

I will be walking the kokan coastline towards the end of the year. It is in a bid to save up the coastline. For that you can donate through paypal - here’s the link.

“We have all known the long loneliness and we have learned that the only solution is love and that love comes with community.”

― Dorothy Day

You can buy my book about my 1800 km walk through India through my website.

There is one more thing by the way.

Most of you joined this Substack after reading stories from Saving a Village. In that series, I spoke about the urgency of taking action against the looming threats of deforestation, coastal highway projects, and the chemical and oil factories set to rise in this eco-sensitive zone. These developments could devastate many villages, including mine. That’s why I’ve decided to embark on a 500-kilometer journey across this stretch of land.

My purpose isn’t political, nor am I here to point fingers at specific companies or factories. Instead, I want to visit each village, sharing the message that while change is inevitable, it’s vital that we steer it in the right direction. I have no desire to cast myself as a hero; my goal is simply to witness this land and its fading culture before it's too late. However, if I can raise awareness and ignite even a small spark of understanding, I’ll be content knowing I did what I could.

But I can't do this alone. To plan the walk and cover necessary supplies, I need your support. Unfortunately, platforms like Kickstarter and other crowdfunding sites aren't available to me here in India, so I’m relying on your donations. You can contribute through PayPal—here’s the link. For donations over $30, I’d love to send you a personalized postcard as a token of gratitude.

I’ll delve deeper into this journey in the upcoming newsletters. Thank you for your support!

Your word paint a picture. I feel that I see it through your eyes. Thank you.

This is a beautiful article, thank you for writing it.